The Dabbawalas of Mumbai are legendary.

These 5,000 people deliver over 200,000 lunches a day to the workers of Bombay, and have done so for almost 125 years. It is not so much what they do that is remarkable, but the process in which they do it. As someone who has spent years of my life looking at how to refine processes in large corporates, I found them fascinating. So did Harvard Business School who apparently now includes a case study on them as part of their curriculum.

So why are they so fascinating?

Here are some facts:

- The majority of dabbawalas are either illiterate or do not read English.

-

All the delivery addresses are written in English.

-

Each individual tiffin box (the container carrying the food) will pass through at least 6 different hands before it reaches its destination.

-

This is all achieved within the space of three hours, in which one package can travel about 30 kilometres (which for anyone who has been in Bombay traffic can appreciate how long that may take in a car).

-

The cost of delivery for each package is about Rs20 ($0.36).

-

The process used has been found to have Six Sigma success rate of over 99%.

For those who enjoy my usual tales of travels or discussions on culture, my apologies but I am going to indulge my geeky side today and take you through some process (I promise to write a second post that goes through the day I spent observing how the tiffins were created).

So back to process, how does this work?

Labelling

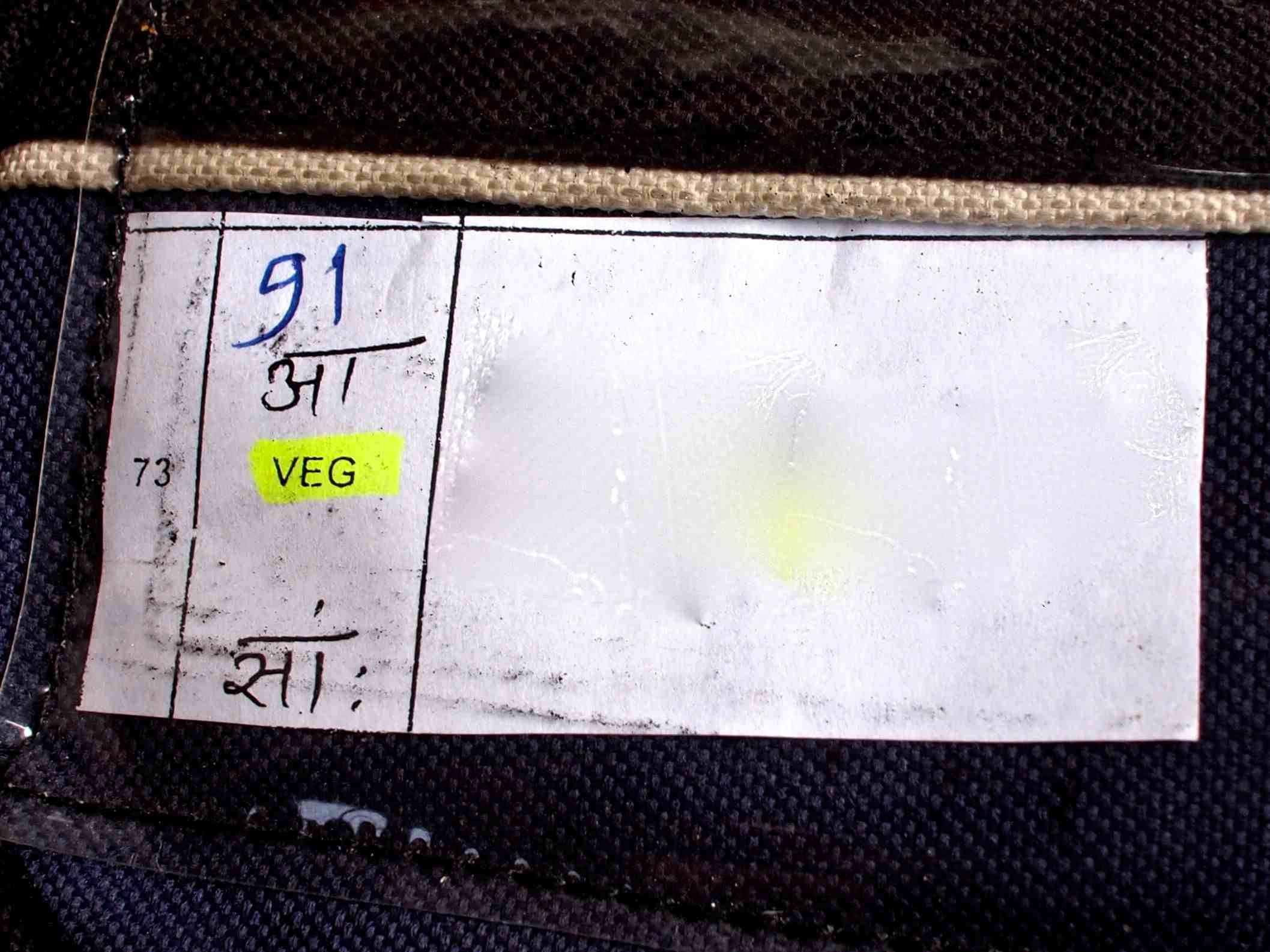

The most important part of the dabbawala’s process is the label. Mobile phones or any other kinds of communication devices are not relied upon or used in this process at all, it is all down to the label. Each label looks like this:

Now the blank space on the right usually has a person’s name, building name (because this is important in any Bombay address), street address, floor etc. So this may have said: Rakhee Ghelani

Bombay Building, Level 2

85 India Street

Churchgate

On the left side are 4 different marks, 3 that are written in Hindi:

The first one indicates the number assigned to the building code, floor number and the code assigned to the individual dabbawala who will deliver the tiffin to the end customer.

The second one indicates which is the final train station and street that the tiffin must go to.

The third one is for the end customer to see that they have been given the correct type of meal (vegetarian or non-vegetarian).

The fourth code indicated the main hub train station that this tiffin box has to go to first. It is these codes that the dabbawalas use to make sure the right person gets their lunch.

The system relies on a process of getting on the right train, getting off at the right station and giving the box to the right person who can read the building code and knows exactly where it is without needing an address. The process for actually getting on the right trains and off at the correct stations is also a well oiled process chain.

Delivery

As mentioned above, there are at least six people that transfer each package from where they were cooked, to where they will be eaten. The 101 of good process is to have as few touch-points as possible, because each touch-point increases the chance of human error. In this instance, the number of touch-points is required to enable the tiffins to be delivered quickly and cheaply, reducing the amount of travel time for each individual delivery person involved in the chain. The six touch-points are:

- At the source, where someone comes to collect the tiffins, usually on their bike. This is usually also where the labels are created and placed on each box. These were the source guys that I spent time with:

- At the nearest train station, the tiffins are passed onto someone who sorts them into groups to determine which train and direction they need to go (the main sorting here is into North and South directions, and then the particular hub that they need to reach).

-

This person transports the tiffins on the train to the train station hub they need to go to.

-

At the train station hub, another person arranges for the tiffins to go onto whichever train they need to next to reach their final destination.

-

This person transports the tiffins on the train from the train station hub to the final station

-

The person making the final delivery on their bike.

The person making the final delivery can deliver between 25 and 40 tiffins in their region. They all reach the customer by 1pm, just in time for lunch.

It really is a well oiled machine that runs entirely on individuals and pedal power. One of the things that makes it survive even in this day and age is just how reliant it is on everyone doing their thing right. Everyone has to do their bit, otherwise the whole chain falls down and along with it, its reputation. So much so, that all the dabbawalas even take their holidays at the same time. One week in April the entire system shuts down for their annual break. After this short break, everyone is right back on the bike again ready to go.

Of course the other key reliance is on the Mumbai train system. Whilst it is old and quite antiquated in many ways, the Mumbai local moves millions of people everyday. It does occasionally have a bad day though, and then… well many go without lunch.

I found spending time with the Dabbawalas and seeing what they do just amazing. What seems like such a simple concept, delivering a meal, is actually a detailed process that has taken decades to fine tune to the point where it is all but 0.01% perfect!

Leave a Reply